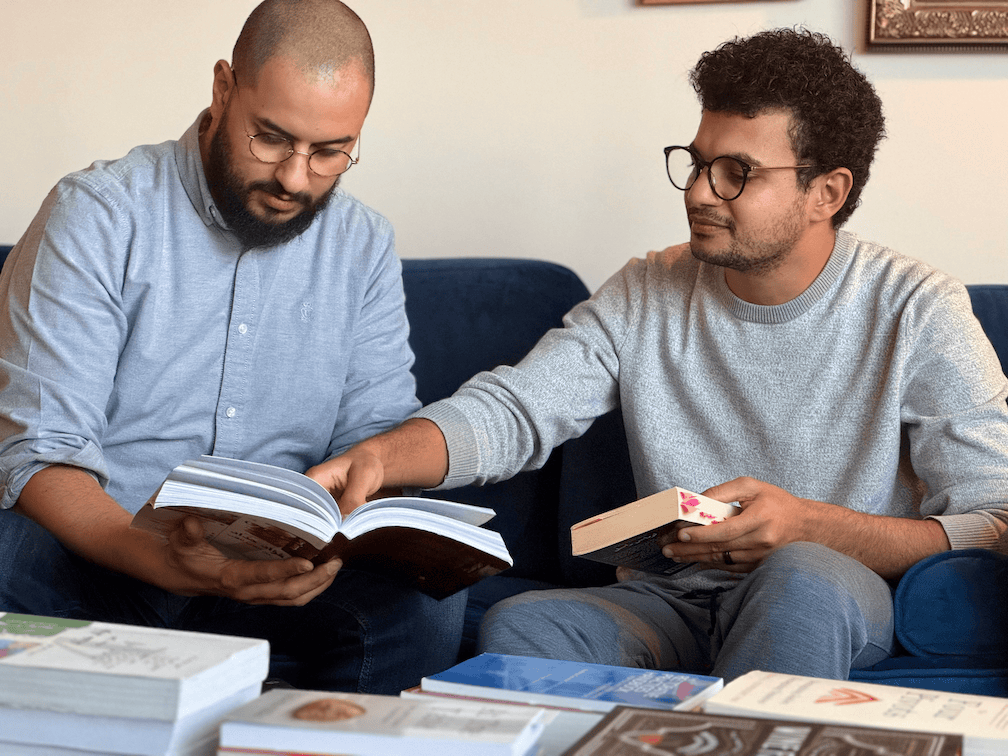

Our Story

Hello! We are Mostafa and Jean-Paul. Just two guys, each with their own unique upbringing and experience of the world. Though something magical binds us together, even before we ever met: Egypt and its rich soul. This is our attempt at conveying our experience of life to the world around us. We aim to share a glimpse of our reality, who we are, and our motivations for trying to bring together the Egyptian, and Arab communities. Soon, we hope to have the opportunity to get to know you as well. To learn about your experiences, your worlds, and your realities. We eagerly anticipate meeting you to enrich both ourselves, and our community as a whole. Our StoriesDawar Darwīsh's Genesis Story“It’s about time to flip that narrative.”

Mostafa’s Story

Growing up with stories and culture around me

My father would come home every day with one or two books in hand, as far back as I can remember. Over time, this habit left us with a vast library spanning various genres, including philosophy, literature, poetry, science, history, religion, and everything in between. My father’s intention was to instill a love for reading in me, so he made me an offer: he would double my pocket money if I read a certain number of pages in the books and explained the ideas to him.

Initially, I embarked on this reading journey with a focus on the monetary incentive. I would diligently read ten pages, carefully summarize the concepts, and then present them to my father in a storytelling manner. True to his word, he would double my pocket money as promised. After repeating this process day after day, something magical happened – I became genuinely captivated by the books. My motivation shifted from earning money to gaining knowledge.

My grandmother played a pivotal role in nurturing my storytelling passion. While my father was at work all day, and my mother busied herself with household tasks, my grandmother eagerly awaited my stories. Every evening at 5 pm, I would sit with her and recount the tales I had read and discovered that day. She would respond with enthusiasm, saying, “Allah, your stories are beautiful, my dear,” and encourage me to share more. This transition, from doing it for the money to finding immense pleasure in the praise and the act of sharing knowledge, was transformative, and it made me feel truly fulfilled.

Ever since I was a little kid, stories have played a significant role in my life. My grandmother, who always treated me as her favorite grandson, would often bring out the family photo album and share stories with me about her father, brothers, mother, uncles, and other relatives, including those who had passed away and those I had never met.

One vivid memory I cherish is riding in a cart with Uncle Essam to the farm, where we would recite poetry and discuss the enchanting world of Adaweyya and Egyptian folklore. Uncle Essam had a group of friends who would come over to our house almost every night of the week. They would hang out, play chess, sing, and just have a great time. During these gatherings, they introduced me to the rich tapestry of Egyptian folklore music and the songs of legends like Karim Mahmoud, Abdelmotalib, Abdelhalim, Oum Kulthoum, Abdelaziz Mahmoud, and many others in the world of Egyptian arts and music. It wasn’t a formal or academic introduction; it happened naturally and mixed with jokes, laughter and stories, reflecting the true essence of our society.

I developed a deep fondness for these songs, and I found that I enjoyed them even more when I experienced them in the company of Uncle Essam and his friends than when I listened to them alone in my room or on my computer. These seemingly small moments left a profound impact on my taste in music and even the way I perceive life itself.

Realizations of the importance of stories in a collective level

Until that moment, I had never truly realized the significance of the stories and individuals in my life. I felt blessed and cherished them, but I considered stories as something ordinary, not particularly exceptional. This perspective remained unchanged until the revolution unfolded, and it exposed me to a new reality.

Egypt had always been like the air I breathed—ever-present but often unnoticed. Years passed, my father passed away in 2002, and my grandmother in 2010. Then, in 2011, the revolution happened. I hailed from a Cairo neighborhood called Saft El-Laban. When I ventured into Tahrir Square during those historic times, I encountered people from all corners of Egypt, each with their unique backgrounds, social classes, religious affiliations, and more—a true reflection of Egypt’s diversity.

However, upon returning home and tuning in to the media coverage, I was struck by a stark disparity. The narrative projected by the media did not capture the essence of our collective dreams and aspirations. It seemed that international media coverage was hijacked by individuals from privileged backgrounds who were fluent in English, thus projecting their perspective rather than the true one. Similarly, in the local media, those with connections to media outlets received disproportionate coverage and exposure. It left us feeling underrepresented and overlooked. It was during this time that I realized the immense importance of storytelling and narrative. It truly is everything; if your story and narrative remain unknown, you remain unknown. This realization underscored the shortcomings of the revolution; the stories and narratives were distorted and failed to represent the vast majority of people who had ignited the revolution. Consequently, it lost momentum and succumbed to the authorities’ suppression.

Why do Egyptians care to tell their stories?

Fast forward to 2017, I arrived in Washington DC to pursue my studies, an experience that profoundly transformed my perspective on life in many ways. However, upon arriving here, I couldn’t help but notice that Egypt seemed to be everywhere I turned. Whether in mentions, statues, signs, or crafts, Egypt’s presence was undeniable. But it left me pondering, which Egypt? It appeared to be predominantly the Egypt of antiquity—a place shrouded in mystery, existing some 10,000 years ago, with its mummies and pharaonic statues. Yet, this portrayal didn’t align with the Egypt I just left behind.

Modern Egypt is a vibrant, living society with its unique perspectives on life and how to navigate it. Despite Egypt’s ubiquitous presence, there exists a significant underrepresentation of what Egypt truly embodies today. Moreover, wherever I go, I encounter Lebanese, Syrian, Turkish, Afghan, Ethiopian restaurants sharing not just their cuisine but also the stories of their societies. Surprisingly, Egyptian establishments are notably absent in this landscape. We are not here, not sharing our stories, not presenting our rich culinary heritage, not showcasing our music and art, nor conveying our contemporary perspectives on life.

It’s about time to flip that narrative.

_______________________

Telling stories is rather a survival need

We are all part of a diaspora, having left loved ones behind and carrying with us the weight of various traumatic experiences. This shared background has sometimes led to suspicion among us, with some assuming the worst in those around them. In a city like Washington DC, where many come from regions of political upheaval and uncertainty, this suspicion can manifest as a belief that others may be informants, government spies, or agents of some sort. You might find this funny of an exaggeration but I assure you this exists, it has happened to me.

Our collective migration here, largely influenced by the Arab Spring and its aftermath, instilled in us the feeling that perhaps nothing is truly worth it. Unfortunately, this sentiment has sometimes resulted in unkind actions and attitudes within the Arab community here. We often interact with exclusion and aggression, driven by our own personal struggles. These actions can lead to hostility and isolation among us, exacerbating feelings of loneliness and estrangement in our adopted society.

وان قيل تاه وضل، وصار الوحيد الاذل، انا وكل الناس هذا الوحيد

When you’re suddenly separated from your circle of friends, the power to narrate your own story is often wrested from your grasp. Consequently, your sense of self becomes shaky, and your entire identity is thrown into question. You begin to ponder, ‘Who am I?'”

I’ve witnessed the unfortunate consequences of people being disconnected without reason, left in isolation and abandonment. It’s during these times that individuals start to doubt their self-worth and lose their confidence, sometimes spiraling into the depths of depression, not long after experiencing social exclusion. This should not be the case.

It’s imperative that we come together, starting from a place of kindness, love, and acceptance. It’s a matter of survival to connect through shared passions such as music, poetry, and art—a space where we can connect on a deeply human and spiritual level.

What do friends provide for each other? They create a space for us to share our stories. They connect with us on a profound emotional level through poetry, music, and intellect. They allow us to express our narratives, whether through spoken words, songs, poetry, or simply by sitting together and listening to music. This is a fundamental human need for surviving the challenges of reality.

Over the years, I’ve been fortunate to find a group of friends who come together to connect through music, poetry, art, laughter, and fun. This space has become essential for us to recharge and feel connected to our inner selves and the people around us.

“These experiences sowed seeds within me.”

Jean-Paul’s Story

Preface

What is reality? What is humanity? Some huge questions that I am sure have crossed all our minds. I think it’s our heritage, our faith, and our experiences. This isn’t another “Power to the Poor” story in which a struggling young Arab overcomes life’s challenges to become Masry-Man and win the Nobel Prize. I’d like us all to take a step back and attempt to look at life from a bird’s eye perspective. Think of how incredibly integrated everyone is. How your life is so real and important to you, but now when you see all lives, how is yours worth more in any way? Doesn’t everyone’s “reality” have validity, at the very least for them? You might have so much in common, but have an extremely different experience, or vise versa. All our worlds are our own and we live in them. In our heads. I have learned to respect this as I want to understand even feel others’ reality, their worlds full of ideas, experiences and emotions. I get to connect on another level and enrich myself with humanity itself.

Way Back When

Amsterdam’s streets blurred past the car window, the canals shimmering under the setting sun. In the backseat, my brother and I fidgeted, our young ears assaulted by the haunting melodies of Um Kulthoum’s “Alf Leila we Leila”. My parents, lost in nostalgia, spoke passionately about the legendary Egyptian singer. The music, so alien to my Dutch upbringing, grated on me. “Can we change it?” I pleaded. My father glanced back, a knowing smile playing on his lips. “One day,” he mused, “you’ll understand its beauty.” The song continued, weaving its magic, leaving an indelible mark on my young heart.

Culture and Community are Lifelines

Growing up as what we now call a Cross Cultural Kid, life was complicated, complex and had many layers. In my case, the conservative culture of my Egyptian, Orthodox Christian family and surroundings hardly matched the culture we grew up in. I, and my many fellow Copts, all grew up together, isolated to a degree. We were each other’s friends and family, each others church buddies, and even sometimes went to the same schools and did the same hobbies. Our parents didn’t do this to isolate us but rather for two main reasons: to protect us from the world around us, and to engrain our religion and heritage in us.

Though Amsterdam is the city of my birth, the essence of Egypt has always coursed through my veins. My parents, with their unwavering commitment, ensured our home echoed with the sounds of Egyptian films, music, and conversations in fluent Arabic. Through my Coptic heritage, I gained a unique lens into Egypt—a connection so deep that I might not have been born in Egypt, but to say “I am Egypt, and Egypt is me” is no exaggeration. The pride, warmth, resilience and dignity of Egyptian patriotism is unparalleled.

Egypt: Bonds Beyond Religion – Family Beyond Blood

Egypt has a complicated history of persecution against the indigenous Copts by their fellow Muslim Egyptians. Although this is by far not a widespread issue, we have witnessed some atrocious events in our recent history. Many of our families had fled Egypt to Amsterdam because of persecution, and so when their children were bullied by fellow Middle Easterners and North Africans in school, because of our Christianity, it only engrained the fear they already had. All my fellow Middle Easterners and Northern Africans wouldn’t accept me because I am a Christian, except for the Egyptians. I cannot stress enough how grateful I am for my Muslim Egyptian friends I grew up with. To this day, they are my family. We were neighbors, schoolmates, worked together, and we connected over our Egyptianness and created a warm community. Each to an extend growing up isolated, the connections we made helped us understand and feel a perspective that we simply didn’t have before. It uncovered each person’s humanity for the other rather than seeing each other as labels. Again, these folks are my family. It’s the love and warmth of my Dutch-Egyptian community as a whole, both Christians and Muslims that helped me and others live and succeed through the society we found ourselves in. We collectively experienced racism and discrimination around us. In addition to our own share of events in The Netherlands and Europe at large, 9/11 might have happened an ocean away, but believe me when I tell you that it had serious effects everywhere, especially in the western world which we were a part of. We also had our own share of events that brought us together closer every time.

Communities come with culture, and ours is as intricate and beautiful as any can get. As youngsters trying to connect with who we are and where we came from, we found solace and connection in the music of Um Kulthoum. She became an icon for the Egyptian cool kids. Slowly but surely, Kawkab al Sharq became a gate for me, which I entered to find numerous other artists that expanded my world. Their ability to capture the essence of Egypt’s soul and convey it through their art was mesmerizing. It became of the things I easily connected over with other Egyptians and Middle Easterners, regardless of religion or background. The older I got and the more I traveled and lived in various places, I learned more about my own history but something integral was missing: I had never visited Egypt.

Finally, at the age of 22 and after a short layover in Zurich, I boarded a plane with one of my life long friends to Cairo. Although it was my first time, I took him and his uncle around Egypt like I was the native. I had my connections to get into places, and was able to meet with great Egyptians, proving my deep connection with my homeland. I simply blended into a Egypt’s fabric as if I was always a part of it. Anyone who’s been to Egypt knows and understands how warm its people are. Now image how it felt for someone born and raised abroad, feeling welcomed home. My first trip to Egypt was wonderous, until it wasn’t but I digress. Balash fadaye7 odam el nas.

But that is exactly what this all comes down to: Egypt is often envisioned through the lens of its ancient wonders, pharaohs, and vast pyramids, with camels wandering the dunes. However, my journey led me to the heart and soul of Egypt—a living, breathing tapestry woven from millennia of enduring cultures, thoughts, and artistic expressions. To many, Egypt might be a chapter in a history book, but to me, it’s a unique and extremely intricate land, people, cultures, thought, music, poetry and literature. Egypt isn’t just a country. She is a symphony of experiences, emotions, and connections.

_______________________

With all this said, no matter where I went, I noticed that we Egyptians and Arabs at large, rarely ever have strong community in the diaspora. It often felt like trying to join an exclusive club, already rife with its own internal dramas. The amount of bickering within the MENA Community at large, and the Egyptian community specifically is just saddening. This often left me feeling isolated and lonely. Yet, amidst this, I was fortunate to cross paths with kindred spirits who embodied the true essence of humanity and compassion. This kept me full of hope, always thinking of how to bring people together, and how to incorporate this Egyptian spirit I felt so strongly through its art and people.

These experiences sowed seeds within me. Over the years, my ideas evolved, shaped by personal experiences and a yearning for community, and somehow wanting to do something with our Egyptian art. Still, these were just all ideas on paper. Then, fate introduced me to Mostafa—a soul who shared my passion for Egypt’s vast artistic heritage and life’s myriad experiences. Our mutual admiration for Sheikh Ahmad Berein gave the spark in our friendship, and through our long days of talking about Egyptian artists, thought, poetry and history, and our shared visions breathed life into The Darwish Society.

Join Mostafa for

The Society’s Genesis Story

Est. 09.15.2023

As we reflect on a exactly 100 years since the passing of Sayed Darwish, we pay tribute to a remarkable artist whose melodies will forever transcend the ages, by establishing this society in his name. Our mission is to tap into the same source of inspiration that is Egypt’s rich, complex, and prolific history of artistic and cultural heritage.

The Name

Our Arabic name for The Darwish Society is دوار درويش – Dawar Darwish, which is inspired by the coming together of a family or community. We aim to become a true community of love, trust and tight knit bonds through Egypt’s artistic soul. Stay tuned to explore and experience this rich history of intense emotions to remind us of the beauty and cultural significance of Egypt’s contributions to humanity.

Our Motto

حلوين على كل حال لكن سوا احلى

“ḥelwein ‘ala kull ḥaal, laken sawa aḥla”

“Content in everyway, but moreso together”.

The Darwīsh Society – Dawar Dawrish

The genesis of this idea can be traced back to a particular afternoon when Jean Paul invited me over. After relishing a delectable meal of Sogo2 balady with Morta Fala7i, we engaged in an extensive hangout where discussions encompassed poetry, music, philosophy, and religion. All the while, Ahmad Berrayn’s rendition of ‘3elbet el-Sabr’ played softly in the background.

It was during this gathering that JP proposed the notion of establishing an official entity, a platform to extend this beautiful space to a broader audience within the DMV area. Through our shared love for art, we had fostered profound and authentic friendships, and now, our aspiration was to reach beyond our immediate circle, he explained. At that moment, the idea of establishing an entity to expand upon this concept had never crossed my mind, but his proposal was both sound and exciting.

We concurred to further explore this idea and brainstorm its potential. Interestingly, during our hangout that day, one of the themes we delved into was the centennial of Sayyid Darwish’s passing. We had intended to pay tribute to his memory and legacy by playing his songs throughout the day, but our shared admiration for Ahmad Berrayn led us in a different musical direction. Nevertheless, when we returned home separately, a serendipitous moment occurred. As I pondered a suitable name for this entity, the term ‘the Darwish circle’ or ‘the Darwish society’ came to mind, and it felt like a brilliant fit. It struck me because in the collective Arab mind, figures associated with the concept of “Darwish-ism” are inherently associated with music, poetry, and Sufism—Sayyid Darwish in music, Mahmoud Darwish in poetry, and the Darwish traditions at large. Just as I was entertaining this thought, Jean Paul messaged me with the question, ‘What do you think about “The Darwish Society” as a name?’ At that precise moment, this telepathic connection we seemed to share felt like a sign that we were moving in the right direction.

Moreover, the esteemed name of the Society in Arabic is “دوار درويش” or “Dawar Darwish.”

The term “Dawar” – “دوار” – is inspired by the circular assembly formed when a family gathers in the abode of the Family Elder, engaging in discussions, sharing tales, telling jokes, or singing harmoniously.

This dwelling, emblematic of the traditional Upper Egyptian “Dawar – دوار العائلة “, stands as a majestic, square or rectangular edifice. At its heart lies a grand square, functioning as either the familial space or the reception chamber. Flanking this central space are multiple tiers, each comprising rooms reached by staircases lining the walls. From every level, one can peer down to the reception hall below, courtesy of the overhanging balconies.

We are committed to creating a space that extends beyond our intimate group to encompass the broader Arab and American communities, both of which yearn for connection and the opportunity to share their stories. This is the essence of The Darwish Society, and it encapsulates the mission we are dedicated to.

يا حبايبنا

فين .. وحشتونا

لسه فاكرينا

ولا نسيتونا

دا حنا فى الغربه

م الهوى دبنا

وأنتو فى الغربه

اوعوا تفكروا

إننا تبنا

مهما فرقونا

ولا بعدونا

يا حبايبنا

Don’t miss out!

Stay up to date with the Society’s upcoming releases and events!